The need for strong privacy regulations in the US is greater than ever.

In the year 2020 alone, data breaches resulting from less-than-adequate security procedures exposed the sensitive data of over 150 million US residents.

And even without data breaches, user privacy is disrespected by many businesses. Over the course of the last three years, we’ve heard about Facebook allowing for ads targeted at children interested in smoking and gambling and Amazon’s Alexa listening to our conversations even when deactivated. We also found out about Google accessing the healthcare information of millions of people without their knowledge, among many other privacy scandals that alarmed the public.

Some of these cases ended up in court. But up until recently, the US regulatory framework didn’t offer any systematic privacy protection for individuals and their data. This, however, is now changing.

Without a comprehensive, blanket solution like GDPR, states are taking the issue into their own hands to create a patchwork that will shape the nation’s future privacy landscape.

In this post we discuss some of the most recent laws, their scope, impact on your analytics and digital marketing activities, and what you can do as a company to ensure compliance.

Laws in the United States

Here’s a list of important privacy legislation, both already in effect and in progress:

- The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) & The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)

- Laws similar to CCPA

- Other privacy laws in the United States

- Data breach notification laws

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) & The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)

Effective date: January 1, 2020 (CCPA) and January 1, 2023 (CPRA)

California’s CCPA is the most notable piece of US legislation affecting digital privacy rights to date. Inspired by GDPR, the act gives residents of America’s most populous state unprecedented transparency and accessibility to data collected by businesses. It focuses on information that is disclosed or sold to third parties, which distinguishes it from its European counterpart.

In 2020, the law was complemented by a new, stricter piece of legislation – The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA). This act will amend and expand on many concepts from CCPA and introduce harsher penalties for non-compliance.

We’ll use informational boxes like this one to show you the differences between your current and future obligations under California’s privacy law.

What’s the law’s scope

The law applies to companies that process personal information from California residents and meet any of the following conditions:

- Have a gross annual revenue of more than $25 million

- Possess the personal information of at least 50,000 California customers, households, or devices

- Derive more than half of annual revenue from selling personal data

CPRA changes the CCPA’s definition of a business. According to the new law, it’s a website, company or organization that:

- Has an annual gross revenue of more than $25 million

- Possesses the personal information of more than 100,000 consumers or households per year

- Derives more than 50% of its annual revenues from selling or sharing consumers’ personal information

17 new privacy laws around the world and how they’ll affect your analytics

Read our recap to learn more about and prepare for 17 new and upcoming data privacy laws from around the world.

How it defines personal information” defined

The CCPA broadly defines PI as anything that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household, including:

- Identifiers such as real name, alias, postal address, unique personal identifier, IP address, email address, account name, social security number, driver’s license number, passport number, or other similar identifiers

- Commercial information, including records of personal property, products or services purchased

- Biometric data

- Internet or other electronic network activity information, including browsing history, search history, and information regarding a consumer’s interaction with a website, application, or advertisement

- Geolocation data

- Education, professional or employment-related information

The key item on this list is “unique personal identifier,” which applies to all cookie-based analytics activities performed on a website.

According to the regulation’s text, it’s a persistent identifier that can be used to recognize a consumer or a device over time and across different services, including but not limited to:

- A device identifier

- Internet Protocol address(es)

- Cookies, beacons, pixel tags, mobile ad identifiers, or similar technology

- Customer number, unique pseudonym, or user alias

- Telephone numbers, or other forms of persistent or probabilistic identifiers that can be used to identify a particular consumer or device

CPRA creates a new category of data – sensitive personal information (SPI). It includes:

- Data on race and ethnicity

- Religious beliefs, political and philosophical convictions

- Data on sex life or sexual orientation

- Genetic and biometric data

- Health data

- Geolocation

- Social security number and driver’s license

- Financial information

Sensitive personal information (SPI) is regulated separately from regular personal information. Users will have more control over that data, including:

- The right to have their SPI disclosed

- The right to opt out from collection of their SPI

You’ll also need to ask individuals for explicit consent for collecting and processing their SPI if they already opted out of tracking that data.

What the law requires

The phrase “consumer request” is found throughout the CCPA and CPRA. Most of the actions on the business side happen after someone has submitted a formal request, but not all of them. The major requirements and provisions are:

- Right to request deletion of their personal information

Under CPRA, the third parties with access to user data, including sensitive personal information, will need to delete it upon user request.

- Right to obtain their personal information collected within the last 12 months

Under CPRA, California residents can request access to PI and SPI collected beyond the original 12 months.

- Right to opt out from the sale of their personal data

Under CPRA, California residents can also opt out of sharing their PI and SPI for behavioral advertising. This also applies to data shared with third parties.

- The opt-in requirement for the sale of data of minors

Under CPRA, the opt-in requirement also includes data used for behavioral advertising.

- Right to data portability

CPRA provides clearer guidance on what’s considered “portable”. The format of data should be easily understandable and accessible for the average consumer. It also adds one more obligation related to data portability – upon customer request, you have to transfer their data to a different business entity, e.g. a bank or an insurance company.

CPRA also introduces some new consumer rights, including:

- Right to correct – consumers can correct inaccurate personal information

- Right to limit use of sensitive personal information – consumers can mandate you to restrict the use of their sensitive data, e.g. not to share it with third parties

- The requirement to wait to re-ask for consent – businesses need to wait at least 12 months before they ask again for the consent to collect personal information of e.g. minors or people who opted out from processing of their sensitive personal information

- Right to know the length of data retention – consumers now have a right to know for how long you want to retain each category of their personal information

Other obligations under CCPA include:

- Privacy policies on businesses’ websites should inform consumers of what categories of personal information they collect and how it’s used.

- California’s residents have the right to sue companies that use data that is stolen or acquired as a result of a breach. In addition, they can also sue companies that were negligent in the handling of their data (for instance, it was not encrypted).

- It’s necessary to provide a clear and conspicuous link on the business’ homepage, titled “Do Not Sell My Personal Information”.

Under CPRA, your homepage also needs to include a link titled “Limit The Use Of My Sensitive Personal Information”.

Actionable steps

- Update your privacy policy – Make sure your policy meets the requirements of the CCPA and that users can easily understand what data you collect and what you and third parties do with it.

- Map your data – A common thread in all privacy laws is the business’s responsibility to track and manage data they’ve collected. To handle data requests in a reasonable time frame, you and your business will need a mapping system you can use to find data.

- Be scrupulous about third-party data and business partners – You will be in violation of the law if you use third-party data obtained from a breach or in another illegal manner. Make sure you always perform due diligence when sourcing from third parties to confirm their legitimacy.

Under CPRA, any third party having access to your collected personal information should be ready to fulfill their obligations related to handling user requests. Examine if your business partners are up to this task and sign a data processing agreement to establish the duties of each party.

- Provide request mechanisms – CCPA requires two methods for consumers to make data requests as well as a “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” link. Make sure your data collection is ready for being corrected, copied, deleted and disclosed in an accessible form.

CPRA also creates a new, similar requirement to provide a link titled “Limit The Use Of My Sensitive Personal Information”. It should enable consumers to limit the use and disclosure of their SPI. CPRA advises that, for consumers’ convenience, both links should be displayed in the same place.

Penalties

As we mentioned in our post about privacy regulations around the world: the new California law also imposes sanctions on businesses that fail to comply with its provisions. The fines include:

- In the case of a suit filed by consumers: $100-750 (or the cost of actual damages, whichever is higher) per resident and incident in the case of breaches or data theft if data was not properly protected.

- In the case of a suit by the State Attorney General: $2,500 per violation and up to $7,500 per intentional violation of privacy.

CPRA transfers the enforcement responsibilities of the Office of the Attorney General to a new government agency, the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA). The new authority will also investigate breaches and violations, as well as draft new regulations.

What’s more, the CPRA cancels the 30-day grace period for businesses that violate the law and increases fines, e.g. for the misuse of children’s personal information. Under CPRA, even an unintentional violation of a child’s privacy can result in fines of up to $7,500.

California Consumer Privacy Act Copycats

Many states are using the California law as a guide for their own legislation. They share most of the same requirements as the CCPA, especially in regard to informing people about data collection, disclosing it upon request, and the broad definition of “personal information.” They’re similar, but not identical – other states have added their own idiosyncratic touches.

A lot of them are putting forward and will adopt CCPA-like solutions in the immediate future. Let’s look at three that are in progress:

Massachusetts Consumer Privacy Bill (S.120)

Effective date: If passed, it would go into effect on January 1, 2023

This state is no stranger to issues with data security: in 2020 alone 2,188 entities reported data breaches affecting 1,087,591 residents (Massachusetts data breach notification reports). The new law aims to prevent this kind of accidents and better protect user privacy.

How’s it different from the CCPA?

This bill is almost identical to its California predecessor: they share the same scope, business requirements, and definitions of personal information. S 120, on the other hand, puts more power in the hands of the people.

Consumers have the right to take legal action against a company. This means Massachusetts residents can sue businesses that violate the safety of their personal information (Mass. S. 120).

New York Privacy Act (S5642)

Effective date: Not passed yet.

New York, home of the NYSE, Yankees, and over 8 million residents. Its new law, currently in the draft form, shares many similarities with the CCPA but has features that make it significantly stricter.

How’s it different from the CCPA?

- Applies to any entity that does business in New York, there are no other criteria

- Establishes that residents can take private action against companies that violate any part of the New York Privacy Act

- Forbids sending personal data to third parties without express and documented consumer consent

Penalties

According to the act, the New York Attorney General would be able to seek civil penalties of up to $15,000.00 per each violation. What’s more, any citizen whose rights had been violated would have a right of private action to recover damages or receive compensation of $1,000.00, whichever is greater.

This wide scope of businesses combined with stricter regulations and the ability for individuals to take action against companies poses a huge threat to those unprepared to securely collect and store personal data.

If you want to gather personal data and share it with third parties, even analytics platforms, you’ will need a way to get permission. Consent managers can automate the process and provide peace of mind.

17 new privacy laws around the world and how they’ll affect your analytics

Read our recap to learn more about and prepare for 17 new and upcoming data privacy laws from around the world.

Other privacy laws in the United States

Other states share the enthusiasm shown by California to protect their residents’ privacy rights and are creating their own unique legislation to accomplish this goal.

Virginia’s Consumer Data Protection Act

Effective date: January 1, 2023

Virginia’s Consumer Data Protection Act (CDPA) was adopted on March 2, 2021. Its passage marks the second-biggest shift in the US privacy framework after California’s CPPA, promising to give Virginia residents more control over how companies use and sell their data. CDPA is a so-called “opt-out law”, which means that under the act, consumers need to take action to object to the collection of their data.

Who is affected by the law

The law applies to every company that does business in Virginia, offers products or services to Virginia residents and:

- Controls or processes the personal data of at least 100,000 consumers during a calendar year

- Controls or processes the personal data of at least 25,000 consumers and makes at least 50% of its gross revenue from the sale of personal data

What’s interesting is that even large businesses won’t be subject to the law if they don’t fall within one of these two categories.

How CDPA defines personal data

Personal data is “any information that is linked to or reasonably linkable to an identified or identifiable natural person”. The law doesn’t provide more guidelines on what’s “reasonably linkable” data. This indicates that it covers all types of identifiable data about an individual, including online identifiers such as cookies or user IDs.

However, CDPA excludes from the scope of personal data:

- Data about employees

- De-identified data

- Publicly available information

CDPA defines publicly available data as any data that was lawfully published through the media by the consumer or a person to whom they have disclosed this information. This could mean that the information disclosed e.g. via social media profiles will be considered publicly available under CDPA.

Your key responsibilities under CDPA

1) Respect the following user rights:

- Right to access

- Right to correct

- Right to delete

- Right to data portability

- Right to opt out

- Right to appeal

These rules have one important exemption. If you want to work with sensitive information, you need the user’s active consent for it. In that case, you need to apply consent mechanisms similar to the ones required by the EU’s GDPR or Brazilian LGPD.

2) Describe your data processing methods in your privacy policy

The law requires you to be transparent about how you collect, process and disclose consumers’ data. In your privacy policy, you need to provide your website visitors with the details on:

- The categories of personal data you process

- The categories of personal data you share with third parties

- The categories of third party you share personal data with

- The purpose(s) for which you process personal data

- How you make it possible for consumers to exercise their rights (e.g. to delete, access or correct their data)

3) Limit the use and collection of data

You need to limit the scope of collected data to what is “adequate, relevant and reasonably necessary in relation to the purposes for which the data is processed.”

4) Apply technical safeguards to your data

You must implement a process for ensuring the confidentiality, integrity and accessibility of personal data. That said, the act isn’t specific about the preferred methods.

5) Perform data protection assessments

You should run data protection assessments that help you evaluate the potential risks of data processing. You can find a comprehensive list of activities here.

6) Sign data processing agreements with every party processing data on your behalf

You need to sign a data processing agreement with every party that has access to data you collect about consumers. The agreement must include the following elements:

- Clear instructions for processing the data

- The nature and purpose of processing

- The type of the processed data

- The duration of processing

- The rights and obligations of the parties involved

Penalties for non-compliance

CDPA doesn’t give consumers the power to take private legal action in case of a privacy violation. Fines are imposed by the attorney general and preceded with a 30-day grace period. If after this time the organization is still in breach of the law, it can face fines of up to $7,500 per violation.

Nevada Chapter 603A Security and Privacy of Personal Information and SB 220

Effective date: July 1, 2017 (SB 220 – October 1, 2019)

Nevada’s laws are already in place. 603A passed in 2017, and in 2019 the state passed amendment SB 220 to deal with the issue of data sold to third parties.

We can break down Nevada’s 603A and amendment SB 220 into three sections:

1. Security of information maintained by data collectors and other businesses

Section 1 applies to data collectors, defined as: any business entity or association that, for any purpose handles, collects, disseminates or otherwise deals with nonpublic personal information.

The key takeaway is that companies which handle or store personal information need to take reasonable security measures. It serves to ensure the safety of people’s data and destroy it if no longer in use.

The law defines personal information as a person’s first name and last name (unencrypted) along with any of the following:

- User name or email address and password that would grant access to an online account

- Social security number

- Driver’s license or identification number

- Combination of account number and password, allowing access to a financial account

- Medical ID or insurance number

A business that handles Nevada residents’ information within this scope of NRS-603A is required to:

- Take reasonable steps towards destroying records containing personal information that are no longer needed

- Maintain security measures to prevent unauthorized access to personal information

- Notify those affected in the event of a data breach

2. Notice regarding the privacy of information collected from consumers

This section establishes the need for a privacy policy that clearly states how you process users’ data. The law requires operators to provide consumers with an understandable explanation of what covered information the website gathers (see definitions below).

Note that covered information is not the same as the personal information.

The definitions of these three terms are:

Operator – owns a website for commercial purposes, or that collects “covered information”

Consumer – a person who seeks or acquires any good, service, for personal, family or household purposes from the website or online service of an operator

Covered information – A broad scope of data that includes any of the following:

- First and last name

- Physical address

- Email address

- Telephone number

- Social security number

- An identifier that allows a specific person to be contacted either physically or online

- Any other information concerning a person collected via the website or online service and stored in combination with an identifier that makes the information personally identifiable

3. SB 220: an amendment to the law

In February 2019 an addition to 603A was introduced to address businesses selling covered information to third parties. The bill gives residents of Nevada the right to opt out by stating:

A consumer may, at any time, submit a notice to an operator directing the operator not to sell any covered information the operator has collected or will collect about the consumer (SB-220).

The bill doesn’t clarify if a business has to implement any opt-out mechanism on their website. That said, many companies have preemptively added them to ensure compliance with the law. Here’s an example:

Actionable steps

Nevada’s law demands a lot. Here’s what can you do to meet the challenge:

- Update your privacy policy – When it comes to getting yours “up to code,” the required information is similar to CCPA or GDPR. Companies need to clarify what categories of covered information they collect, describe how users can review/request changes, and disclose any third parties with access. Here you can also provide a “do not sell my data” opt-out.

- Increase security – Incorporating measures that protect your data collection and storage activities is crucial. By encrypting data, it’s no longer considered personal information. You should use data encryption systematically and work to prevent any data breaches.

- Map your data – A common thread in all privacy regulations is the business’s responsibility to track and manage users’ data. To handle data requests in a reasonable time frame, you and your business will need a mapping system that locates data quickly.

Penalties

Enforcement is the responsibility of the Nevada Attorney General, not individuals. According to the law, any operator that directly or indirectly violates NRS 603A may face:

- A civil penalty not to exceed $5,000 for each violation

- A temporary or permanent injunction

With any reasonably successful website having thousands of visitors a month, it’s easy to imagine $5,000 per violation quickly adding up to an astronomical sum.

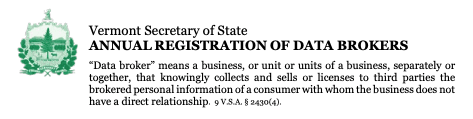

Vermont Act 171 Data broker regulation

Effective date: January 1, 2019

The first of its kind to establish a set of rules for data brokers – companies that gather and sell consumer data to third parties. This Vermont regulation is breaking new ground. Let’s see what it’s about:

How is a data broker defined?

A data broker is a company, or part of it, that collects and sells brokered personal information of a Vermont consumer they don’t have a direct relationship with.

If you answer “yes” to any of these questions, you should scrutinize your business practices to see if the law defines your business as a data broker:

- Does the business handle the data of consumers with whom they do not have a direct relationship?

- Does the business both collect and sell or license the data?

- Is the data about consumers who are Vermont residents?

- Is the data brokered personal information? (see definition below)

What is “brokered personal information?”

The regulation considers data as brokered personal information (BPI) if it’s computerized and organized or categorized in some way as preparation for being sold to another business. For example, categorized data such as “people interested in used cars” or “people in Vermont aged 20-30.”

Data or information on paper retained by a business with no intention of selling it doesn’t fall under the definition of BPI.

Act 171 states that data which is digital, ready for sale, and contains one or more of the following is BPI:

- Name

- Address

- Date or place of birth

- Mother’s maiden name

- Biometric information

- Name or address of immediate family member

- Social security or other government-issued ID number

- Other information that would allow consumer identification with reasonable certainty

What does the law require of data brokers?

Data brokers need to take two actions to be in compliance with Vermont’s Act 171:

- Register with the Vermont Secretary of State annually

- Maintain certain minimum data security standards

The law also holds businesses that plan to sell Vermont-sourced BPI to a certain standard of security. Brokers need to develop, implement and maintain a comprehensive program that performs risk assessments, detects system failures, encrypts personal data, and more.

Does Act 171 affect how I acquire data?

Vermont took actions to regulate the illegal acquisition and use of BPI. The law states clearly that it is against the law for any business to:

- Acquire brokered personal information through fraudulent means

- Acquire brokered personal information for:

- Stalking or harassing someone

- Committing fraud, including identity theft, financial fraud, or e-mail fraud

- Engaging in unlawful discrimination, including employment discrimination and housing discrimination

17 new privacy laws around the world and how they’ll affect your analytics

Read our recap to learn more about and prepare for 17 new and upcoming data privacy laws from around the world.

Actionable steps

- If you’re a data broker, register with the state of Vermont: Every year, data brokers must register their business on this page and pay a fee of $100. This is the easiest way to protect yourself from trouble in the future if you deal in the sale of brokered personal information in Vermont.

- Make sure your systems are secure: Confirm that your business meets the requirements of this law. Data encryption, training, and routine checks are the best ways to keep data safe and stay out of hot water.

Penalties

Failure to register as a data broker can result in a fine of up to $10,000 per year. A business or individual who acquires or uses brokered personal information illegally faces the same fine.

Data breach notification laws

All 50 states have adopted legislation that makes it mandatory for companies to inform affected individuals of data breaches that may compromise their personal information. These regulations vary from state to state, with discrepancies in the definition of personal information or notification methods and deadlines.

One breach can leave you grasping at straws trying to assess the damage done and comply with legislation in every state affected.

What’s important is the growing need for companies to adopt a data responsibility mindset.

Apart from compliance with US privacy laws, Piwik PRO lets you follow the requirements of PIPEDA, the Canadian federal privacy law.

What general measures should you take?

As you can see, these laws are not the same and there’s no “one size fits all” approach to finding a solution to keep your business compliant with different privacy frameworks. There are, however, common themes and aspects in all of them. You can take general measures that will help.

- Appoint a data protection officer – A DPO is responsible for your company’s compliance with laws protecting individuals’ personal data. You need one if you want to be aligned with GDPR, and they can also guide you through the US privacy landscape. It’s a great player to have on your team, and such a complex, high-risk task deserves a specialized employee.

- Be transparent – You need to be open when it comes to collecting data from people. Get consent or provide clear opt-out options, according to the regional laws. Also, rethink and update your privacy policy. It should clarify how you collect and share data, how to opt out of selling, and how to access data for correction or deletion.

- Establish standards for collecting and storing data – When it comes to data and analytics, “the more, the merrier” is usually how we think we should operate. This needs to be rethought. Collecting or holding data, especially PI, that you’re not using is potentially risky and has no business benefit. Strategize: only take and keep what you can use.

- Beef up your security – If you suffer a leak of unencrypted personal information, legally you will be responsible. Encryption is a great step that helps ensure your data isn’t personal or identifiable. Make sure third parties that you cooperate with hold themselves to the same security measures as your business (for example, check the companies’ compliance with ISO 27001 and SOC 2 standards). You need to conduct due diligence before passing information on to other entities.

- Apply privacy by design framework – Moving forward, you need to integrate privacy into the product and service development process. Building with privacy in mind is a proactive step that will keep you out of trouble instead of deploying reactionary measures after it’s too late. This mindset also applies to employee training and office culture. If you handle sensitive data, your staff should operate accordingly.

How Piwik PRO Analytics Suite helps you comply with US privacy laws:

- Get full control over collected data

- Quickly set up banners to inform visitors about the collection of their data and give them a way to opt out and send data requests

- Collect and process user requests using Piwik PRO Consent Manager

- If needed, set up consent banners using Piwik PRO Consent Manager

- Store data on secure infrastructure on public cloud, private cloud (dedicated database), private cloud (dedicated hardware) or on-premises (in your own cloud subscription with one of our certified cloud providers)

Conclusion

Europe took the first step, but America isn’t far behind. More and more states and countries are enacting privacy legislations. Soon, it will become almost impossible to keep operating without rethinking how you handle consumers’ data. The best thing to do is to take action and be prepared, as this new wave of legislation appears to be a long-term progression rather than a short-lived trend.

Additional reading:

10 new privacy laws around the world and how they’ll affect your analytics →

PIPEDA & CPPA: How the Canadian privacy laws impact your analytics →

What is privacy-friendly analytics? →