We Europeans love cookies. There is Italian cantuccini, German lebkuchen, French navette and Dutch stroopwafels. But love only goes so far.

A type of cookie we’re not a fan of is the digital cookie. Cookies on the internet are used to remember our preferences or track us across the World Wide Web. This can have some serious privacy implications. That’s why the European Union has a strict set of rules that govern the use of cookies. (And there’s more to come!)

Most of the time, when people talk about online consent, they think about cookies. Cookies and consent for their use are governed, on a European level, by two regulatory instruments: the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the ePrivacy Directive.

Both instruments depend (partly) on national interpretation – the directive because it depends on national implementation and the GDPR because it grants countries some freedom in certain areas. This means that rules for cookie consent can vary across the member states.

This blog post sets out to explain the concept of cookie consent in the EU, the rules that are in place in different countries and tips on cookie banner best practices.

Consent under the GDPR

Consent can only be used as a legal basis for processing when it is a freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes. It must be given by clear affirmative action. This applies to all kinds of data processing, including the processing of data with cookies.

When asking for consent, companies should inform the data subject about the types of cookies they use and what they use them for. Furthermore, they can’t force visitors to grant consent. No negative consequences may arise from refusing to give consent.

There are some exceptions where cookie consent isn’t required under the GDPR, specifically:

- For cookies whose sole purpose is to carry out the transmission of a communication over a network. This means cookies that are used to identify endpoints and allow for data to be transferred between devices.

- For cookies that are essential to provide an information society service requested by the user. This means cookies that remember the content of your cart or your preferred language.

In November 2023, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) formulated guidelines outlining the new technical scope of Art. 5 (3) of the ePrivacy Directive. According to this article, companies must obtain prior consent before storing or accessing information on a user’s electronic device unless it is necessary to provide the requested service. So far, this principle has mainly applied to Internet cookies. The recent guidelines significantly extend the list of technologies covered by Art. 5 (3) to include new tracking methods and technical operations.

The EDPB focuses on five critical elements of the cookie rule and applies an extensive interpretation to all of them:

- Information includes both non-personal and personal data, regardless of how it is stored or by whom.

- Terminal equipment refers to equipment connected to the public telecommunications network, e.g., smartphones, laptops, connected cars, connected TVs, or smart glasses.

- An electronic communications network is any system that allows the transmission of electronic signals. The rule concerns public communication services provided over such networks. However, communication over a network available to a limited number of people (e.g., subscribers) is also considered public.

- Access – the EDPB has a very broad delimitation of access according to which an access exists if an entity actively takes steps to gain access to information stored on a terminal equipment.

- Storage applies to information of any type, in any quantity, and takes place over any time (even as short as storage in RAM or CPU cache).

In this context, the “cookie rule” in the ePrivacy Directive would also apply to technologies such as URL and pixel tracking (including “identifiers”), local processing, tracking based on IP only, JavaScript code, Internet of Things (IoT) reporting, and other device fingerprinting techniques.

The EDPB’s proposals have sparked controversy as they may negatively affect the market. It was reflected in the feedback from various industry bodies as part of the public consultation on the new guidelines.

To quote The Federation of European Data and Marketing:

The EDPB’s broad interpretation of “gaining access” would (…) mean that every communication over the internet is somehow “gaining access” to information within scope of Art 5(3) ePD (…). In doing so, the draft Guidelines’ interpretation also captures technologies and basic technical operations which are not necessarily related to marketing or advertising purposes (…). It is therefore unclear how a consent requirement for non-intrusive technical operations which do not necessarily involve the processing of personal data would bring a better protection of privacy to the user. This also seems detrimental to the user’s online experience as they will be asked to engage with additional consent requests, likely exacerbating the so-called “consent fatigue” .

The Central Association of the German Advertising Industry ZAW noted the need for a risk-based approach in the new guidelines. The IAB brought up, among other things, the negligence of the technical considerations.

Nevertheless, the guidelines reflect the EU data protection authorities’ interpretation of the law and are not directly binding. The outcome of the EDPB’s efforts to enforce the guidelines is yet to be determined.

Implied consent

We’ve all seen websites with a cookie banner stating that “by using this site, you agree to the use of cookies”. This concept is called ‘implied consent’. The rationale behind implied consent is simple: if you don’t want cookies, don’t visit this website.

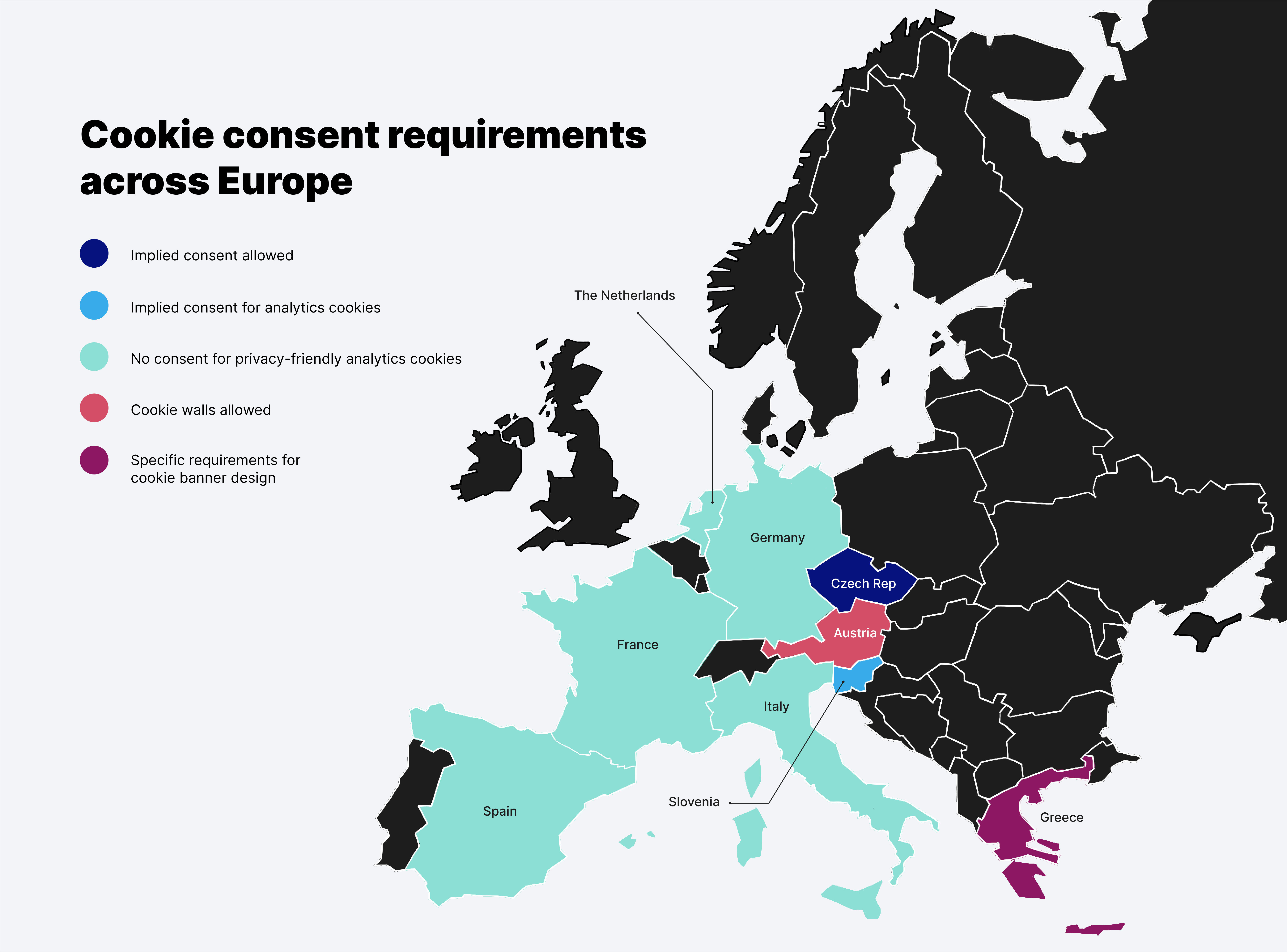

Most EU member states prohibit this practice. But some of them, such as the Czech Republic, Italy, and Slovenia, allow implied consent under certain conditions:

- The Czech Republic puts a lot of trust in the technical skills of its citizens. If you don’t set up your browser to automatically refuse cookies, you give your implied consent to use them [1].

- Italy puts its own spin on implied consent. Inactivity on the user’s part or simply scrolling down a webpage is not regarded as consent. However, when scrolling down a website is part of a complex series of actions that form a specific pattern clearly showing the choice of the user to the owner of the website, it can be treated as consent [2]. This type of consent puts a heavy burden of proof on the website owner.

- Slovenia is the third country that knows a form of implied consent. Implied consent is assumed for privacy-friendly analytical cookies.

Consent for analytical cookies

Is consent needed for analytical cookies? We already saw that Slovenia assumes implied consent for privacy-friendly analytical cookies. But how about other Member States?

Europe is divided with regard to this issue. The basic rule is that consent is needed for analytical cookies because they’re not regarded as purely functional cookies. Some Member States, however, allow the use of analytical cookies without consent.

For example, the Netherlands, Italy, and France allow the use of analytical cookies without consent when these cookies are privacy-friendly.

What are privacy-friendly analytical cookies?

What are privacy-friendly analytical cookies?

Again, the rules may vary a bit between the Member States, but the general rule is: the statistics may only be used for your own website, and they must safeguard the privacy rights of visitors.

For example, in the Netherlands, analytical cookies are only privacy-friendly if they use anonymized IP addresses and don’t create User IDs. Furthermore, sharing analytical data with other parties for advertising should also be disabled.

Germany and Spain, like the Netherlands, Italy, and France, also allow the use of privacy-friendly analytical cookies without consent, but only if they are first-party cookies. This means that the analytical cookies and the software behind them must be hosted on servers belonging to the website owner. So, for Germany and Spain, an on-premises solution, such as one offered by Piwik PRO, is required.

Using privacy-friendly analytical cookies is always a good move. Even if a country still requires consent, users are perhaps more likely to give it when their privacy isn’t at stake.

So, clearly inform your website’s visitors about how important analytical cookies are for the development and maintenance of your site and that you’re using privacy-friendly analytical cookies. If you are transparent and give them the ability to make their choice, there is a good chance they will agree.

If you’d like to learn more about privacy-friendly analytics, be sure to read this blog post: What is privacy-friendly analytics?

Cookie walls

Consent or get out! A cookie banner that blocks all content until you give your consent is not allowed. This is one of the rules most European countries agree on (or haven’t shared their opinion on yet).

Austria is the only member state with a limited exception to this ban on cookie walls. News websites can have a cookie wall if they provide an alternative option to pay for access to the article or a subscription to the website.

This exception is a topic of discussion in more member states. This makes it something to keep an eye out for.

Welcome to the jungle: layout

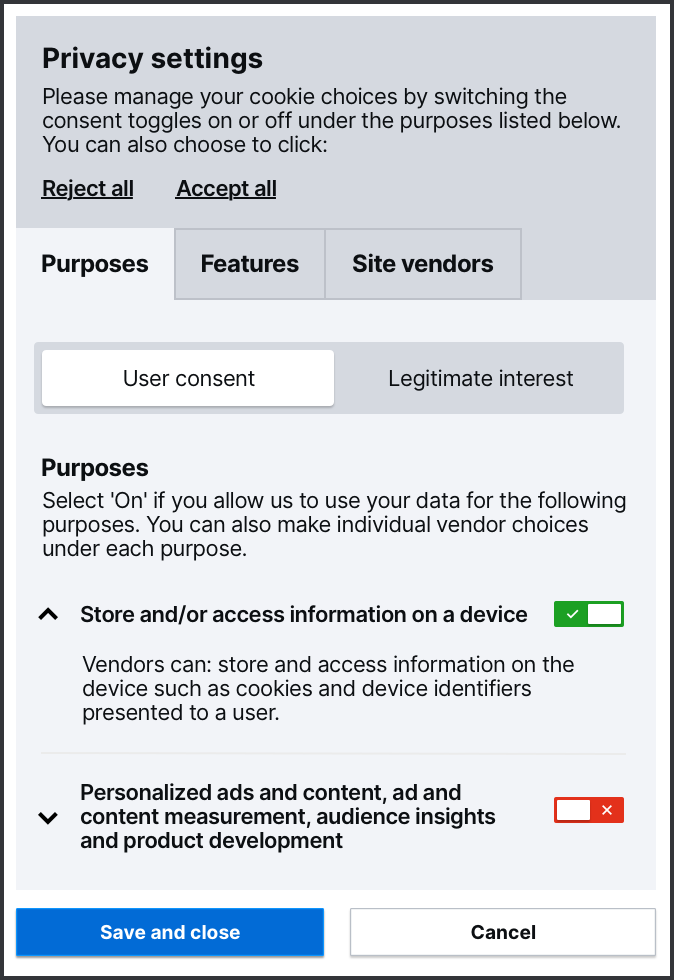

With some cookie banners, you can’t see the forest for the trees. You have to navigate a jungle of checkboxes, toggles, and buttons to indicate that you don’t want cookies.

Even though granular consent must be an option, making a cookie banner hard to navigate and understand is not permitted under the GDPR. The GDPR requires the information to be clear and unambiguous. As a rule of thumb, you could say that a hard-to-navigate cookie banner makes for unclear information.

Companies should avoid those long and very granular cookie banners. Not only because they’re frustrating for customers/users and make the information unclear, but also because of the judgment by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in the Planet49 case.

In this judgment, the CJEU concluded that using pre-checked boxes doesn’t constitute valid consent under the GDPR. Companies can’t ‘help’ their users by pre-checking all boxes – users must do it themselves.

The reason for this is that consent must be an affirmative action. This judgment has deprived cookie-banner jungles of their charm. In the past, you could theoretically use a cookie banner with a thousand pre-ticked boxes, and nobody would deselect them all. Now, you could add a thousand boxes, but they should all be empty. Only true fans of your service would tick a thousand boxes just so they could give you their personal data.

Even if pre-ticked boxes were still allowed, using extensive and detailed cookie banners is not allowed under the GDPR. The GDPR states that giving consent should be just as easy as not giving consent. When using an elaborate and complicated cookie banner with individual reject buttons but a single accept all button, what is harder to do – giving or not giving your consent?

So, don’t use complicated cookie banners, and don’t use pre-ticked boxes.

Learn more about CJEU consent requirement rulings: The CJEU sheds more light on trackers and consent requirements

Best practices for cookie consent banners

We’ve discussed the don’ts, but what about the dos? Just like the other things we’ve already mentioned, there are EU-wide dos and local dos.

At the very least, a cookie banner should include:

- Information on what categories of cookies will be installed, by whom, and for what purpose.

- A link to your privacy policy.

Some countries, however, have specific rules on what a cookie banner must look like. Take Greece, for example. In Greece, the visitor’s choice shouldn’t be affected by the website’s design (so accept and reject buttons should preferably be the same size and color).

To help you remember the differences in cookie consent requirements between EU countries, here is a breakdown of what we’ve discussed:

You might also like: When design goes awry – How dark patterns conflict with GDPR and CCPA

Cookie consent in the EU – Final remarks

Even though cookies are governed by EU legislation, there are a lot of differences across countries, creating a diverse cookie consent landscape.

For the last couple of years, the EU legislator has been working on the ePrivacy Regulation to provide a single set of rules that apply to every EU state. But until this regulation is in force, we are faced with diverse and frequently changing rules. Data protection authorities regularly publish new guidelines and case laws that could impact how you use cookies.

Even though this is subject to change, it’s always a good idea to follow these guidelines in your cookie consent banner:

- Don’t use cookie walls

- Don’t use implied consent

- Don’t use complicated cookie banners

- Don’t use pre-ticked boxes

- Don’t make it hard (or impossible) for users to reject cookies

- Use privacy-friendly analytics

- Provide an informative and clear cookie banner

- Add a link to your privacy policy

If you want to make sure you’re doing everything by the book, contact ICTRecht at info@privacyverified.nl. It’s always possible to talk about your options over a nice cup of coffee and some cookies (that you can easily reject!).

Additional reading: